I love Monster Hunter: Wilds. The monsters are massive; the fights are dynamic. Even after forty hours, I’m still flinching each time a monster makes a dramatic appearance or strikes unexpectedly. This game is an absolute blast, an excellent addition to Capcom’s Monster Hunter franchise… and yet.

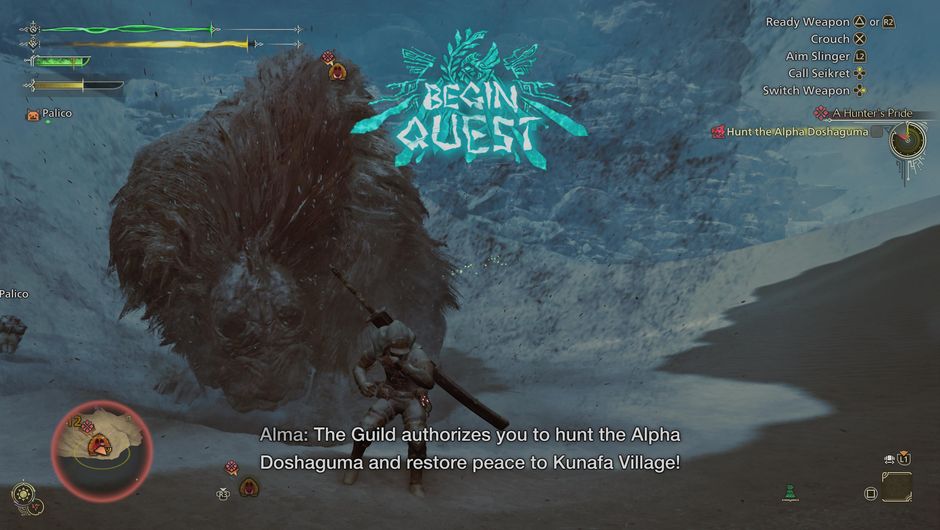

Monster Hunter: Wilds‘ story rubs me the wrong way. Question: who within the Hunters Guild has the authority to authorize a monster hunt? Throughout the game, influential characters permit the player to kill or capture monsters. I recall that NPC characters Alma, Olivia, Erik, and Fabius have individually authorized hunts… Narratively speaking, my character is an experienced hunter who has more than proven herself formidable in battle. Who would stop me if I took it upon myself to hunt without direct authorization? Actually, to that point, I have hunted creatures in the Wilds without explicit permission. I can jump from my Seikret (wyvern mount) to strike down regularly appearing Chatacabra in the Plains region at almost any time. Are those actions unauthorized? Does initiating an incidental quest on a haphazard monster suggest that the guild has somehow approved my request to hunt? I completed no paperwork in those few airborne moments before landing atop a wild monster. So what, then, are the criteria for authorization?

This may be an unusual hill to die on. (So to speak.) However, I maintain there are ethical questions worth mulling when a game’s core mechanics and narrative revolve around hunting wildlife in an unfamiliar environment home to civilizations your party does not know or understand. Monster Hunter: Wilds uses a guild authorization system to distance the player from culpability and its endorsement of colonizing tactics while invading another person’s native land.

Monster Hunter: Wilds uses a guild authorization system to distance the player from culpability and its endorsement of colonizing tactics

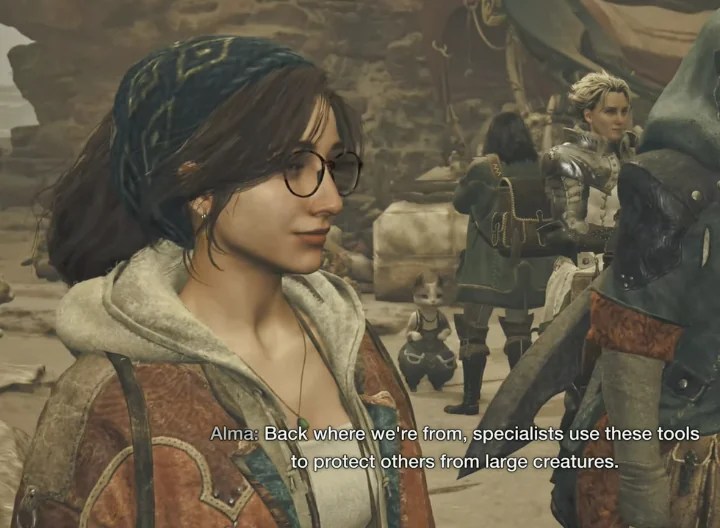

Monster Hunter: Wilds begins by plunking “civilized” explorers down on “primitive” foreign soil. In the game’s opening cinematic, an exploratory sandship discovers an unconscious boy in an uncharted desert who claims to belong to a semi-mythical clan known as “The Keepers.” The boy reports that his people were recently dispersed by a dreadful creature called “The White Wraith.” The boy, Nata, asks for help finding his clan and saving them from this terrible monster. Astounded that anyone inhabits the region, let alone the legendary Keepers, the Guild sends the player’s Hunter character to assist.

History repeats when a young girl atop a Seikret (wyvern) intersects the desert sandship pursued by Capcom’s equivalent of sandworms. The girl, Nona, reports that her brother Y’sai is fending off a large monster in a cave and needs help. This time, the player is present. The player receives authorization to hunt the monster, though it is quickly determined that Nona and her brother are not Keepers and that the monster in question is not The White Wraith. Happily, saving and reuniting Nona and her brother Y’sai by slaying the Chatacabra (colossal frog monster) earns the player’s party passage to Kunafa village, another society novel to the Guild.

Wind Chimes?

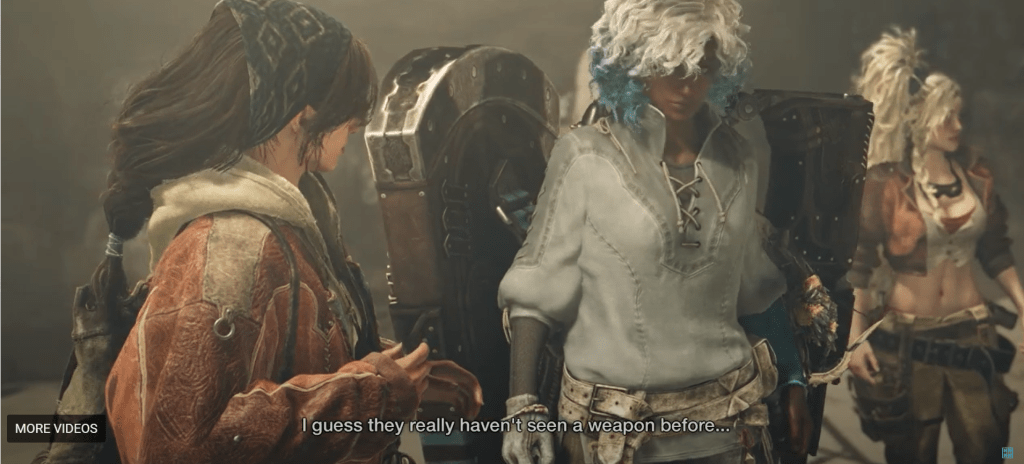

Kunafa village was my first red flag. Inside Kunafa, villagers dressed in simple garb accented with frayed threads and bone decorations, despite inexplicably speaking your native tongue, marvel at your weapons: “What’s that on [their] back? It’s huge!” In response, your companion Alma, dressed in an oversized hoodie, glasses, and tasteful modern jewelry, reasons: “I guess they really haven’t seen a weapon before.” The story asserts that the people of Kunafa utilize a system of wind chimes to dissuade the hulking monsters that roam the surrounding areas from attacking the village and that they have never needed to develop weapons. However, when a rogue Doshaguma (colossal bear-lion-dog monster) invades shortly thereafter, it’s up to the player, authorized by the Guild, to spare these weaponless noble savages.

“Noble” Kunafa

According to Britannica, a “noble savage, in literature, [is] an idealized concept of uncivilized man, who symbolizes the innate goodness of one not exposed to the corrupting influences of civilization.” The vision of the “noble savage” is nothing new. While the term is more commonly associated with 18th and 19th century political and philosophical Western thought, similar narratives can be found in ancient Greco-Roman literature. (I’m looking at you Xenophon and Pliny.) This romanticized portrayal of foreign cultures is problematic because it imposes an unrealistic standard of idyllic simplicity onto Indigenous people. By equating this depicted simplicity with purity, we not only infantilize Indigenous culture but also confine their identity to a past era, labeling them as ‘behind the times,’ ‘primitive,’ or even ‘backward.’ Through this lens, the manipulative actions of ‘more civilized’ people become easier to justify. Suddenly, hunting on behalf of a struggling village is seen as necessary, since its people supposedly lack the means to protect themselves. Continued intervention in unfamiliar lands feels warranted because the inhabitants are perceived as incapable of handling complex threats. Even adopting their gestures, speech, and fashion seems acceptable—after all, they are quaint people who have shared their food with you.

By equating… simplicity with purity, we not only infantilize Indigenous culture but also confine their identity to a past era

And the player is free from any concern about culpability or complicity—after all, the Guild has given its approval.

Authorizing Acknowledgement

Opinions on Reddit and Steam Community forums vary, as they often do. Some users express skepticism that a remote village surrounded by kaiju-like monsters wouldn’t have developed weapons, while others defend the impressive logistics behind Kunafa’s advanced windchime mechanism. Many dismiss the story entirely, arguing that Monster Hunter’s writing has always been secondary to its action—a sentiment I generally share. However, Wilds appears to be a sequel to a previous installment, and dedicated fans have reveled in its narrative confirmations and expanded lore. Given that the storyline is grounded in lore, unskippable, and features significant writing and cinematic effort, it’s clear that the developers approached it with intention. Moreover, with Monster Hunter Wilds selling over 8 million copies within just three days—making it the fastest-selling game in Capcom’s history—the company has received strong validation for its creative choices.

Conclusion

By many standards, Monster Hunter: Wilds is a great game. One of my favorite moments comes early in the story—fighting the Alpha Doshaguma in the desert amid a raging sand-and-lightning storm: My view of the world is cast in shadow, sand whipping around my Hunter as lightning lances at my feet. Ahead, the hulking silhouette of the monster—massive jaws agape, dripping, ready to strike—lunges at me. I am solitary, minuscule by comparison. I remember feeling awestruck by the sheer sublimity of the moment—just before my character was smashed dramatically into the dunes.

Yet, Monster Hunter: Wilds also presents a deeply problematic narrative. The Guild, often arbitrarily, authorizes the disruption of unknown ecosystems and the infantilization of Indigenous culture sans consequence. The player character outsources their responsibility to the disembodied “Guild” by waiting to receive authorization.

the danger lies in overlooking or passively endorsing questionable, even unethical, ideologies

I do believe it is possible to enjoy a game while acknowledging its ethical shortcomings. Like people, games can be multifaceted. Monster Hunter can be a good game and have a bad story. However, the danger lies in overlooking or passively endorsing questionable, even unethical, ideologies, especially in monstrous AAA titles that reach millions of people around the world and generate millions of dollars for companies. We have a responsibility as consumers to call out these inequities when we see them, to show developers that we see these depictions as immoral and undesired, even while we play the game and enjoy larger-than-life encounters fighting monsters.

So… Hunter! The Guild authorizes you to reflect on its perception of Kunafa (and Azuz and The Keepers and…) and the possible ramifications of colonizing Indigenous lands.

Leave a comment